In the quiet halls of museums and the brittle pages of centuries-old sketchbooks, a revolution was being drawn one line at a time. The Renaissance, a period celebrated for its explosive creativity in painting and sculpture, harbored a deeper, more meticulous secret within the preparatory sketches of its masters. This was not merely practice; it was a profound intellectual and artistic inquiry into the very architecture of life. The humble drawing, often a means to an end, became the primary cipher for a new understanding of the human form, a language of lines that evolved from idealized symbolism to empirical truth.

The story begins in the workshops of Florence and Venice, where the medieval tradition still cast a long shadow. Early Renaissance draftsmen, while striving for greater naturalism, often worked from classical models and established conventions. The human figure was frequently constructed through a system of geometric shapes and proportional canons, a holdover from a worldview that sought perfect, divine harmony in all things. Anatomy was implied rather than investigated, a series of elegant curves suggesting muscle and bone beneath drapery or skin. The line was confident but generalized, serving beauty and ideal form above all else. It was a code of aesthetics, one that spoke of a world ordered by philosophical principles rather than physical dissection.

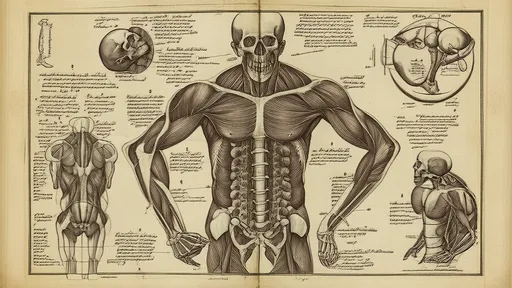

This began to change as a new spirit of inquiry, humanism, took root. With it came a renewed interest in the individual and the natural world. Artists were no longer content to rely on the inherited wisdom of the ancients or the church; they wanted to see for themselves. The catalyst for the most dramatic evolution in drawing was the scalpel. Gaining permission to dissect human cadavers—often under the cover of night and amidst considerable moral and legal controversy—artists like Antonio del Pollaiuolo and later, the unparalleled Leonardo da Vinci, embarked on a gruesome but transformative journey. They moved from observing the outside to mapping the inside.

Leonardo’s notebooks are the Rosetta Stone for this cryptographic shift. His pages are a chaotic, brilliant fusion of art and science. A single sheet might contain a perfectly rendered study of a dissected leg, its layers of muscle, tendon, and bone meticulously cross-hatched to convey volume and texture, alongside philosophical musings on the soul and precise engineering diagrams for flying machines. His line evolved into an instrument of scientific notation. He used different weights of line—lighter for superficial layers, darker and more emphatic for deep-lying structures—creating a visual hierarchy on the page. His famous Vitruvian Man is the ultimate expression of this fusion: the idealized geometric proportions of the ancient world superimposed upon a figure whose musculature is rendered with the acute observation of a dissector. The line here is both a measure of perfect beauty and a record of biological fact.

Meanwhile, in Rome, Michelangelo Buonarroti was pursuing the same truths but with a dramatically different emotional charge. For Michelangelo, anatomy was not merely a subject of study; it was the key to expressing intense spiritual and psychological drama. His surviving drawings, particularly his studies for the Sistine Chapel ceiling and later works like The Last Judgment, show a relentless focus on the male torso. His line is more aggressive, more physical. He clawed at the paper with his pen, using dense, parallel and cross-hatched lines to build up forms that seem to burst with pent-up energy. He was less interested in the clinical labeling of parts than in how those parts worked together under strain, in torsion, and in repose to convey passion, anguish, or divine wrath. His figures are not simply anatomically correct; they are anatomically expressive. The密码 (code) in his work is one of emotion, written in the language of straining deltoids and contorted abdominals.

This fervent activity in Italy did not go unnoticed across the Alps. Northern artists, particularly the Germans, absorbed these lessons and interpreted them through their own lens of meticulous detail and graphic intensity. Albrecht Dürer, after his travels to Italy, became obsessed with proportion and anatomy, producing exhaustive theoretical treatises. His drawings, such as his famous Praying Hands, display a different kind of line—incredibly precise, controlled, and analytical. He used line to document the specific, undramatic truth of veins, wrinkles, and bone structure with an almost unflinching objectivity. In contrast, artists like Matthias Grünewald used their anatomical knowledge to achieve shocking levels of visceral realism, most notably in the tortured, crucified body of Christ in the Isenheim Altarpiece, where the line describes suffering in brutally biological terms.

As the Renaissance waned, the knowledge pioneered by these masters became part of the foundational training for all artists. Academies were established, and the life drawing class, with its focus on the live model, became a staple. The act of drawing from the nude was now an exercise in applying this hard-won anatomical understanding. The line had completed its journey. It was no longer a secret code deciphered by a few intrepid geniuses in clandestine dissecting rooms. It was now the essential grammar of artistic education. The frantic, exploratory hatches of Leonardo and the powerful, emotive contours of Michelangelo were formalized into a system of shading and description that allowed artists to convincingly render the human form from memory and imagination.

The legacy of this evolution is imprinted on the entire history of Western art. Every dynamic Baroque saint, every serene Neoclassical goddess, and even the distorted figures of Modernism that rebelled against it, are all in a conversation with the discoveries made on those parchment pages. The Renaissance draftsmen, through their relentless study, performed a remarkable alchemy. They transformed the cold, objective facts of flesh and bone into a language of unparalleled beauty, power, and emotion. They proved that the deepest truths could be found not by looking away from the body's reality, but by gazing ever deeper into its mysteries, one deliberate, revolutionary line at a time. The密码 was cracked, and in doing so, they gave art a new voice.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025