In the heart of China's Henan province, where the Yi River cuts through the landscape, the Longmen Grottoes stand as a monumental testament to human devotion and artistic mastery. Carved into limestone cliffs over several dynasties, these caves house one of the most impressive collections of Chinese Buddhist art, with tens of thousands of statues and inscriptions that narrate a spiritual journey spanning centuries. Among the many practices dedicated to preserving and understanding this heritage, the on-site rubbing of Buddhist statues emerges as a particularly profound discipline—one that bridges ancient craftsmanship with contemporary scholarly pursuit.

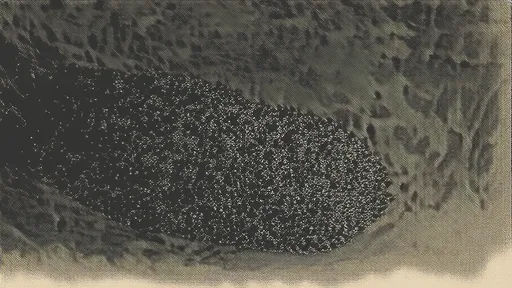

The art of rubbing, or ta in Chinese, is an age-old technique used to create precise copies of engraved surfaces. For the Longmen Grottoes, this process is not merely about replication; it is an intimate dialogue with the past. Specialists engage in this meticulous work directly at the site, carefully applying moistened paper to the contours of the statues, then tapping ink onto the surface to capture every detail—from the serene expressions of the Buddhas to the intricate patterns adorning their robes. This hands-on approach demands not only technical skill but also a deep reverence for the cultural and religious significance of the sculptures.

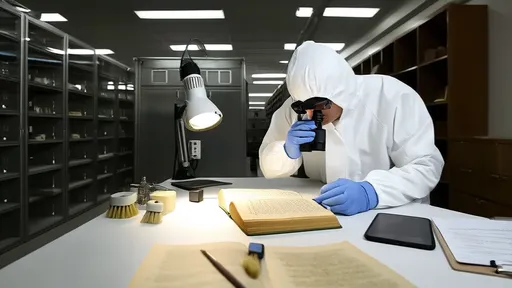

What sets the on-site rubbing practice at Longmen apart is its immersive nature. Unlike digital scans or photographs, which can sometimes flatten the experience, rubbing requires the practitioner to be physically present, to feel the texture of the stone, and to respond to the unique challenges posed by each statue's condition and placement. It is a sensory engagement that fosters a unique connection between the artist-scholar and the ancient carvers. The resulting rubbings are not just copies; they are artifacts in their own right, bearing the marks of both the original creation and the contemporary hand that carefully documented it.

The process begins with preparation, where the team assesses the statue's stability and surface to ensure no harm comes to the ancient stone. They then select specialized paper—often xuan paper, known for its durability and sensitivity—which is softened and molded onto the sculpture using brushes and water. This step alone can take hours, as the paper must conform perfectly to every groove and curve without tearing. Once dried, the ink application begins, layer by layer, with practitioners using tampons to gently dab ink, building up contrast and clarity until the image emerges with startling precision.

These rubbings serve multiple purposes beyond preservation. They are vital tools for academic research, allowing scholars to study iconographic details, stylistic evolution, and even epigraphic inscriptions that might be weathered or obscured in situ. Moreover, they provide access to remote or fragile sections of the grottoes that are no longer easily reachable or safe to examine closely. In this way, the rubbings become a portable archive, enabling continued study and appreciation without risking further damage to the originals.

Yet the practice is not without its controversies. Critics have raised concerns about potential damage to the statues from repeated contact, despite the careful protocols in place. In response, practitioners emphasize the non-invasive materials and techniques developed over generations, arguing that when done correctly, rubbing is one of the least intrusive methods of documentation. The debate underscores a larger tension in heritage conservation: how to balance access and study with the imperative to protect these irreplaceable treasures.

Beyond academia, the rubbings from Longmen have found a place in cultural diplomacy and public education. Exhibitions around the world feature these works, showcasing the grandeur of Chinese Buddhist art to audiences who may never set foot in the grottoes. They also play a role in local communities, where they help foster a sense of pride and continuity, linking modern residents to the profound historical and spiritual legacy literally carved into their surroundings.

Looking forward, the tradition of on-site rubbing at Longmen is evolving. New technologies like 3D scanning and high-resolution photography offer complementary tools, but many argue that the tactile, artisan-based approach of rubbing provides insights that machines cannot replicate. Training the next generation in these skills remains a priority, ensuring that this unique blend of art and scholarship does not fade into obsolescence. It is a living practice, adapting to contemporary needs while honoring ancient methods.

In the end, the on-site rubbing of Buddhist statues at the Longmen Grottoes is more than a technical procedure; it is a meditative act of preservation. Each rubbing captures not only the physical form of the statues but also the echoes of the devotion that created them. As these works continue to be studied and displayed, they carry forward the spiritual and artistic legacy of Longmen, allowing future generations to engage with one of humanity's great cultural achievements in a deeply personal and tangible way.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025