In the quiet neighborhoods of aging cities, a silent transformation is taking place. It begins not with the roar of bulldozers or the erection of gleaming steel frames, but with a subtle, almost meditative attention to the scars of time: the cracks in our walls. The Old Wall Renovation Plan, a movement gaining traction among architects, artists, and community activists, proposes a radical shift in perspective. It posits that these fractures are not merely structural flaws to be concealed, but narratives in their own right—opportunities for creative intervention, storytelling, and the reclamation of urban memory.

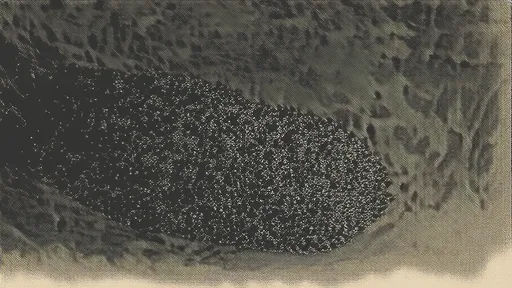

For decades, the standard protocol for dealing with cracked walls, whether in historic buildings or modest homes, has been one of eradication. Spackle, plaster, and a fresh coat of paint have been the tools of choice, aiming to restore a facade of seamless perfection. This approach, while practical, is fundamentally subtractive. It removes evidence of a building’s history, its encounters with settling earth, shifting temperatures, and the sheer passage of years. The Old Wall Renovation Plan challenges this notion of perfection, arguing that in smoothing over these imperfections, we erase a layer of the city's biography. The crack becomes a metaphor for the wider neglect of aging infrastructure and the stories embedded within it.

The movement finds its roots in a confluence of disciplines. Japanese kintsugi, the ancient art of repairing broken pottery with lacquer dusted with powdered gold, is a frequent philosophical touchstone. Kintsugi does not disguise the breakage; it highlights it, treating the repair as part of the object's history, making it more beautiful for having been broken. Similarly, the plan advocates for repairs that honor the crack's existence. This isn't about a haphazard or unstable patch job. It is a deliberate, artistic, and structural choice to integrate the flaw into a new, enhanced whole.

Artists are at the forefront of this creative介入 (intervention). Some employ techniques like vector mapping, where the precise lines of a crack are digitized and used as the basis for a larger mural, transforming a random fissure into the central vein of a leaf or the leading edge of a lightning bolt. Others use materials that contrast starkly with the original wall. A deep crack in a red brick wall might be filled with brilliantly colored resin, which is then sanded smooth, creating a glowing, river-like inlay that catches the light. In one notable project in Lisbon, a web of cracks on a building's stucco facade was meticulously traced with thin, illuminated fiber optics, creating a stunning, star-map-like display that glowed softly at night, turning a sign of decay into a public landmark.

Beyond pure aesthetics, these interventions serve a profound social function. In community-led projects, the process of repairing a cracked wall becomes a collaborative act. Residents are invited to contribute materials with personal significance—shattered porcelain from a grandmother's teacup, colored glass from a local beach, fragments of tiles from a demolished school. These materials are then used to fill the cracks, literally weaving the community's history into the very fabric of the building. The repaired wall ceases to be a passive surface and becomes an active archive, a tactile monument to collective memory and resilience. It tells a story of care and attention, a stark contrast to the narratives of urban decline and neglect.

From a purely practical standpoint, these methods can also offer superior solutions. Traditional filler materials often have different expansion and contraction rates than the original wall material. With changes in humidity and temperature, this can lead to the repair failing, with the crack reappearing alongside the patch—a phenomenon known as "ghosting." Some creative interventions solve this by using flexible materials like specialized epoxies or resins that can move with the wall. Furthermore, by widening a crack slightly to create a clean "V" groove (a process known as v-cutting) before filling it with a durable, decorative material, the bond becomes stronger and more permanent than a simple surface-level cover-up.

The plan also dovetails with urgent environmental concerns. The ethos of "creative repair" is inherently sustainable. It champions adaptation and reuse over demolition and replacement, dramatically reducing the carbon footprint associated with new construction materials and waste haulage. A wall that might have been deemed unsightly and scheduled for costly demolition and rebuilding is instead given a new lease on life through a fraction of the material and energy expenditure. This approach aligns with circular economy principles, viewing "waste" not as an end-product but as a resource for new creation.

Of course, the plan is not a panacea. Significant structural damage requires serious engineering solutions, not an artistic gesture. Proponents are careful to stress that their work begins only after a thorough assessment by structural engineers has confirmed that a crack is superficial or stable. The creative intervention is then applied as the final, visible layer of a sound structural repair. The challenge lies in navigating building codes and convincing conservative planning committees that a glowing resin-filled fissure or a gold-leafed crack is not a sign of shoddy workmanship but a conscious design choice with cultural and structural merit.

The impact of the Old Wall Renovation Plan is ultimately measured in more than just repaired surfaces. It fosters a different way of seeing our urban environment. A daily commute becomes a tour through an open-air gallery of repaired histories. It encourages citizens to look closer, to find beauty and potential in the broken and the aged. It cultivates a culture of maintenance and care over one of disposal and renewal. In a world increasingly obsessed with the new, the sleek, and the flawless, this plan is a quiet revolution. It teaches us that our walls, like ourselves, are marked by their experiences, and that there is profound strength and beauty in acknowledging those scars, not hiding them. The crack is not an end; it is a beginning.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025