The art of printmaking has long been celebrated for its intricate techniques and the profound depth it brings to visual storytelling. Among these methods, the copperplate aquatint, specifically the rosin dust technique, stands out for its unique ability to produce rich, nuanced gray tones that are difficult to achieve through other means. This process, which hinges on the meticulous control of rosin particles, allows artists to create works with remarkable tonal range and subtle gradations, evoking a sense of atmosphere and emotion that is both delicate and powerful.

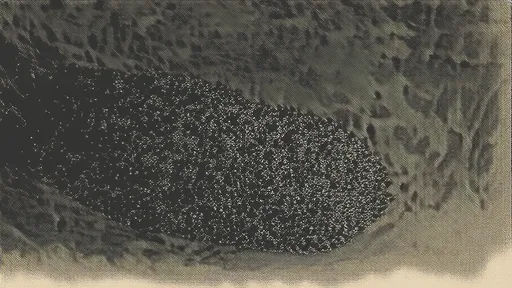

At the heart of this technique lies the use of rosin, a brittle, translucent resin derived from pine trees. The rosin is ground into a fine powder, and its particles are then evenly distributed across the surface of a copper plate. The size and density of these particles are critical, as they directly influence the tonal values in the final print. Larger or more densely packed particles will resist acid biting more effectively, resulting in lighter areas, while smaller or sparser particles allow for deeper etching and darker tones. Mastering this balance is where the true artistry begins, requiring not only technical skill but also an intuitive understanding of how minute variations can impact the overall composition.

The process begins with the careful preparation of the copper plate. It must be impeccably clean and polished to ensure that the rosin adheres uniformly. The rosin dust is then applied using a dust box, a specialized container designed to create a cloud of fine particles. The plate is placed inside, and the rosin is allowed to settle over it. The duration of this settling process, along with the fineness of the rosin grit, are variables the printmaker must control with precision. Too brief a exposure results in a sparse distribution, leading to overly dark and potentially blotchy tones after etching. Conversely, excessive settling can create a layer that is too thick, yielding faint, washed-out grays that lack definition.

Once the plate is coated to the artist's satisfaction, it is gently heated from below. This stage is deceptively simple yet fraught with peril. The goal is to melt the rosin particles just enough so they fuse to the copper plate, forming an acid-resistant ground. The heat must be applied evenly and at a controlled temperature. If the heat is too low, the particles will not adhere properly and may flake off during etching. If it is too high, the rosin will liquefy entirely, pooling and breaking up the delicate, granular texture that is essential for creating the desired aquatint grain. The ideal outcome is a microscopic, honeycomb-like pattern of hardened rosin dots, perfectly bonded to the plate.

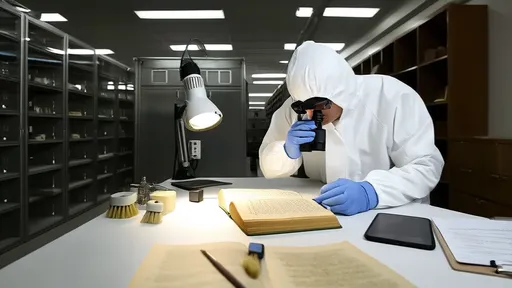

With the ground securely in place, the plate is ready for the acid bath. The artist submerges it in a solution, typically nitric acid or Dutch mordant, which bites into the exposed copper between the rosin particles. This is where the magic of tonal control truly unfolds. The artist does not simply leave the plate in the acid for a fixed time. Instead, they employ a method known as "stopping out." After an initial biting period that establishes the darkest tones, the plate is removed from the bath. The artist then uses a varnish to paint over and protect the areas that have reached the desired depth of etch—the areas that will print as the darkest grays or blacks. The plate is returned to the acid, and the process is repeated, protecting successively lighter tones after each bite. This painstaking, incremental approach allows for the creation of a full spectrum of grays, from the deepest shadows to the most ethereal highlights.

The final result is a plate etched with a complex topography of tiny pits and plateaus. When ink is applied, it fills these etched areas. The surface is then wiped clean, leaving ink only in the recesses. Under the immense pressure of an intaglio press, damp paper is forced into these ink-filled cavities, transferring the image. The printed image reveals the artist's success in controlling the rosin grain. A well-executed aquatint will display smooth, seamless transitions between tones, devoid of the harsh lines of an engraving or the fuzzy quality of a mezzotint. It possesses a velvety, matte finish that is uniquely its own, capable of rendering the soft diffusion of mist, the subtle modeling of a form, or the dramatic contrast of light and shadow with unparalleled elegance.

In conclusion, the rosin dust technique for controlling gray tones in copperplate aquatint is a testament to the marriage of scientific precision and artistic vision. It is a demanding discipline that rewards patience and a meticulous hand. From the initial grinding of the rosin to the final pull of the press, every step is an exercise in controlled chaos, a negotiation between the artist's intent and the material's behavior. The resulting prints are not merely images but physical artifacts of this intricate dance, holding within their gray scales a world of emotion, atmosphere, and breathtaking subtlety. It is a process that continues to captivate and challenge artists, preserving a rich tradition of printmaking excellence.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025