In the ever-evolving world of art, few techniques have managed to carve out as distinct and tactile a niche as the impasto method in oil painting. Often referred to as thick painting or heavy body application, this approach transcends mere visual representation to engage the viewer on a profoundly physical level. The very term impasto originates from the Italian word for 'paste' or 'mixture,' a fitting description for a technique where paint is laid on a surface in exceptionally thick layers, often so pronounced that the brush or knife strokes are visibly and tangibly evident. This is not merely painting; it is a form of sculpting with pigment, a deliberate and revolutionary embrace of texture as a primary element of artistic expression.

The history of applying paint thickly is not a modern invention. One can trace its early, tentative beginnings to the works of masters like Rembrandt van Rijn and later, Francisco Goya, who used heavier applications to add depth and luminosity to specific elements, such as jewelry, fabrics, or the grimaces on the faces of his dark subjects. However, these were often isolated accents within a larger, more traditionally smooth composition. The true revolution, the moment when the technique burst forth from the constraints of mere detail and became the very soul of the artwork, arrived with the dawn of the 20th century and the advent of Modernism. It was the Dutch post-impressionist Vincent van Gogh who arguably became its most famous early pioneer. For Van Gogh, the swirling, tormented, and exuberant ridges of paint were not a stylistic choice but a physiological necessity. They were the direct, unfiltered transcriptions of his emotional turmoil and his ecstatic vision of the world around him. In masterpieces like The Starry Night, the paint itself seems to be alive, churning with the energy of the cosmos, making the viewer feel the wind and the movement of the stars through its thick, undulating surface.

This liberation of texture was seized upon and pushed to its logical extreme by the Abstract Expressionists in the mid-20th century. Artists like Willem de Kooning and, most notably, Jackson Pollock (with his drip paintings that built up complex sedimentary layers) began to treat the canvas not as a window into another world but as an arena in which to act. The resulting work was a record of that action, its thick, chaotic topography a map of the artist's creative process. Yet, it was the reclusive artist Jean-Michel Basquiat in the 1980s who brought a raw, visceral energy back to the figure using impasto. His paintings are archaeological sites of meaning, built up with layer upon layer of paint, text, and symbolism, where the thick, cracked surfaces feel like urban walls, scarred and layered with history and graffiti.

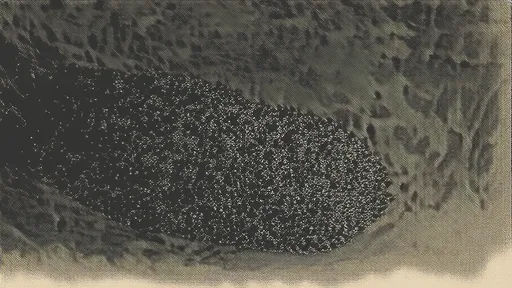

The allure of impasto lies in this unique dialogue it creates between the artwork and its audience. A traditionally smooth, glazed painting is viewed; an impasto painting is experienced. The thick layers of pigment interact with light in a dynamic dance, creating highlights and shadows that change with the viewer's perspective and the ambient light in the room. This gives the painting a living quality, a presence that shifts and evolves throughout the day. The texture invites touch, even if museum rules forbid it. There is an innate human desire to trace the ridges left by a palette knife or feel the peak of a hardened brushstroke, to physically connect with the artist's gesture frozen in time. This haptic quality—the ability to appeal to the sense of touch through sight—is the core of its power. It breaks down the barrier between the illusory space of the painting and the real, three-dimensional space of the viewer.

Mastering this textural revolution requires more than just enthusiasm; it demands a deep understanding of materials and technique. Not all paints are created equal for this purpose. Oil paints are the quintessential medium for impasto due to their slow drying time, buttery consistency, and ability to hold a peak without slumping. Within the oil category, artists often seek out brands with a high pigment load and a stiff, malleable body. To augment the texture further and make the expensive pigment go further, various mediums can be incorporated. Traditional beeswax mediums add body and matte finish, while modern molding pastes and compounds can be mixed in to create extreme textures that remain flexible and crack-resistant over time. The tools of application are just as crucial. While brushes can be used, the true instruments of impasto are painting knives—metal blades of various shapes and sizes that allow the artist to slice, spread, and sculpt the paint with surgical precision or wild abandon.

The process itself is a lesson in patience and chemistry. The foundational principle is 'fat over lean'. This golden rule of oil painting dictates that each subsequent layer should contain more oil (be 'fatter') than the one beneath it. This ensures proper drying and adhesion, preventing the upper layers from cracking as they dry faster than the oil-rich layers below. When building up extreme textures, artists must work patiently, sometimes allowing layers to set up to a leather-hard state before applying the next, to prevent colors from muddying and forms from collapsing. The drying time for a heavily impastoed painting is not measured in days, but in months or even years, as the outer skin can dry while the interior remains soft, slowly oxidizing over a long period.

In the contemporary art scene, the tactile revolution of impasto is far from a historical footnote. It is more vibrant and relevant than ever, continually being redefined by a new generation of artists. Some, like the Italian painter Nicola Samori, use thick layers only to then scrape, peel, and scarify them, creating haunting, palimpsest-like surfaces that speak of decay and memory. Others use impasto with hyperrealistic precision, building up textures so detailed they mimic reality itself from a distance, only to reveal their abstract, tumultuous nature upon closer inspection. The technique has also found a fervent following in the world of plein air painting, where artists use thick, rapid strokes to capture the fleeting energy and light of a landscape directly from life, the texture embodying the wind, the heat, and the immediacy of the moment. Ultimately, the revolution of impasto texture is a celebration of materiality. In an increasingly digital and virtual world, the physical, almost primal presence of a heavily textured painting serves as a powerful reminder of the artist's hand. It reaffirms the objecthood of the artwork, its existence as a unique, tangible thing crafted from raw materials. It is a technique that demands to be seen in person, as reproductions flatly fail to capture its depth, its shadow play, and its visceral invitation. To stand before a great impasto painting is to witness the artist's struggle and joy made manifest, a topographical record of creation where every ridge and valley tells a story of its making. It is a testament to the enduring power of touch, a revolution not just in how we see art, but in how we feel it.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025