In the vast tapestry of global fashion, few garments have journeyed as far and transformed as dramatically as the humble marinière, or as it is more commonly known today, the Breton stripe shirt. What began as a functional uniform for French sailors has, over two centuries, navigated the complex currents of culture, politics, and style to become a ubiquitous symbol of effortless cool from the boulevards of Paris to the bustling streets of Tokyo and Seoul. Its voyage is not merely one of geography but of meaning, a story of how clothing can be adopted, adapted, and utterly reimagined as it crosses borders and generations.

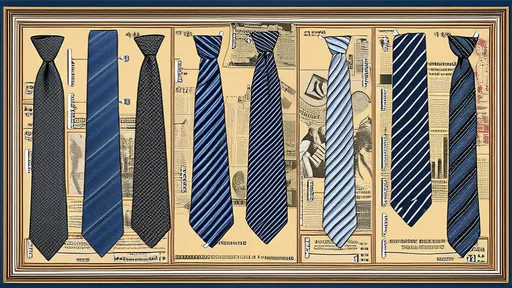

The shirt's origins are firmly anchored in practicality. On March 27, 1858, an official ordinance of the French Navy decreed that a tricot rayé (striped knit sweater) would become standard issue for all its sailors. The specifications were precise: the shirt was to be made of white cotton or wool with 21 blue stripes, each stripe representing one of Napoleon Bonaparte's victories. The dark blue and white pattern was chosen for high visibility, making it easier to spot a man who had fallen overboard in the choppy waters of the Atlantic and the English Channel. This utilitarian beginning in the port city of Brittany is what gifted the garment its enduring name: the Breton shirt.

Its transition from naval deck to cultural icon began in the early 20th century, thanks largely to the bohemian artists and intellectuals who flocked to the Normandy coast. They saw in the marinière not just a piece of clothing, but a symbol of a romantic, salt-sprayed life, a stark contrast to the rigid formality of urban attire. The shirt was effectively "discovered" by the fashion world when the legendary Coco Chanel, inspired by the nautical wear of the French sailors she observed in Deauville, incorporated it into her groundbreaking 1917 resort collection. Chanel, a pioneer in borrowing elements from menswear, presented the striped top as the epitome of casual, liberated elegance. It was a revolutionary act, transforming a working-class garment into a high-fashion statement for the modern, independent woman.

The shirt's symbolic power was further amplified on the silver screen. Perhaps its most iconic cinematic moment came from the French actor and singer Jean-Paul Belmondo, who wore one in Jean-Luc Godard's 1960 New Wave classic, À Bout de Souffle (Breathless). On him, the marinière became a uniform for the rebellious, anti-establishment cool of the era. But it was the image of a young, pixie-cut Audrey Hepburn, lounging in a striped top and capri pants, that truly launched it into the international stratosphere. She embodied a chic, gamine sensibility that was both approachable and impossibly stylish. Later, figures like Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol, and Brigitte Bardot would be photographed in their Breton shirts, each layering it with their own personal mythology and cementing its status as a timeless staple of the French wardrobe—a symbol of intellectual and artistic nonchalance.

The garment's journey eastward began as Western pop culture started to permeate Asian markets in the latter half of the 20th century. The same films that made the marinière iconic in Europe and America also captured the imagination of youth in Japan and South Korea. However, its adoption was not a simple act of imitation. In Japan, during the economic boom of the 1980s, there was a profound fascination with European, and particularly French, lifestyle and aesthetics—a concept known as Francophilia. The Breton stripe, or Burūton shatsu (ブルトンシャツ), was absorbed into this trend. But Japanese fashion designers and consumers are never mere copyists; they are masterful interpreters. The shirt was often re-engineered with a distinct Japanese sensibility—slimmer cuts, finer gauge knits, and sometimes integrated into more avant-garde, deconstructed ensembles that played with proportion and tradition.

In South Korea, the shirt's integration has been turbocharged by the Hallyu wave—the global rise of Korean pop culture. K-Pop idols and actors are among the most influential fashion trendsetters in Asia, and their stylists frequently use the Breton stripe to craft a specific image: one that is modern, sophisticated, and effortlessly stylish. It appears in music videos, on variety shows, and in the off-duty street style of celebrities, signaling a kind of international, cosmopolitan flair. Unlike its historical association with artistic rebellion in the West, in the hyper-stylized context of Korean pop culture, the marinière is often used to convey a more polished, yet accessible, form of cool. It’s less about overthrowing the establishment and more about being impeccably current.

Today, on the streets of Harajuku in Tokyo or Myeongdong in Seoul, the Breton shirt is a common sight, but it is rarely worn in its "pure," classic form. It has been wholeheartedly embraced by the streetwear scene, which is the dominant force in contemporary Asian youth fashion. Here, the shirt is mixed, matched, and layered in ways its original designers could never have imagined. It might be worn oversized, tucked into wide-leg cargo pants, paired with technical vests and chunky sneakers. It's tied around the waist, knotted at the front, or layered under a hoodie. Designers like Comme des Garçons (under its PLAY line with the iconic heart logo) have created their own iterations, further legitimizing its place within high-fashion streetwear. The 21 stripes are no longer a historical footnote but a graphic element to be played with, a component in a larger style lexicon that values individuality and reference.

The global journey of the marinière is a powerful case study in cultural transmission. It demonstrates how an item of clothing can be completely divorced from its original context and imbued with new layers of significance. From a functional sailor's uniform to a symbol of French chic, and then to a versatile staple of global streetwear, its meaning is constantly in flux. It is no longer exclusively French; it is a citizen of the world. Its stripes now tell a new story—one of global interconnectedness, of the endless cycle of inspiration and reinvention that defines modern fashion. It proves that some of the most enduring style icons are not those that remain static, but those that are brave enough to travel, adapt, and be transformed by every shore they touch.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025